While you should normally begin plotting a story by understanding the threat to your main characters (i.e. the villain), let's start with the hero.

Protagonist Traits

Have you ever heard a reader complain that a main character is "unlikable" or "boring"? If a reader says this about your main character, that can be some devastating feedback.

Your reader will be spending the most time with your protagonist, so this character is essential to get right. Regardless of personality, each protagonist needs at least one of these traits for the readership to want them to succeed.

Your reader will be spending the most time with your protagonist, so this character is essential to get right. Regardless of personality, each protagonist needs at least one of these traits for the readership to want them to succeed.

- Likability

- Competence

- Determination

Likability: Could you be friends with this character?

This trait defines how their personality comes across to the audience. Obviously, this is one of the most YMMV scales, as different people find different personalities likable.

Likability doesn't mean the character is perfect, or always nice. It means their flaws balance their personality. Aladdin may be a thief and a liar, but one of his first actions is to give his hard-earned food to a couple of kids who need it more, showing his generosity. Even rough characters usually get a "pet the dog" moment somewhere early on that proves the audience did the right thing in wanting them to win.

Likability doesn't mean the character is perfect, or always nice. It means their flaws balance their personality. Aladdin may be a thief and a liar, but one of his first actions is to give his hard-earned food to a couple of kids who need it more, showing his generosity. Even rough characters usually get a "pet the dog" moment somewhere early on that proves the audience did the right thing in wanting them to win.

Arrogant, broody types can vary pretty far on the scale of likability. Some people find them enjoyable, and others not so much. If you want to boost likability for your arrogant or loner protagonist, counter it with other positive traits, like loyalty or generosity. Wit and a sense of humor or snark can also be a good boost, depending on your story's tone and your audience.

If readers' mileage varies so much, how do you determine your character's likability? Find out how this character handles relationships, and how they balance other people vs. themselves. Their likability is probably going to take a hit if background characters are disposable, if they push away their friends frequently or in cruel ways, or if they're always sacrificing their relationships to do what they think is best for themselves.

Competence: How good are they at what they do?

It's fun to watch people succeed! MacGuyver types are especially exciting as they solve almost any problem with chewing gum and a paper clip.

Especially if your antagonist is powerful, it's nice to see someone be able to counter them. It makes it clearer why your protagonist fills that role, if they are the only one who can outwit or outfight the villain.

Also, there's a very important reason certain audiences loved "Captain Marvel" and "Black Panther" so much. It's fantastic to watch people who look like you fight evil and oppression so effortlessly. And, more importantly, it's deeply satisfying. Readers are looking for that kind of fist-pumping moment, whatever the genre or audience.

Also, there's a very important reason certain audiences loved "Captain Marvel" and "Black Panther" so much. It's fantastic to watch people who look like you fight evil and oppression so effortlessly. And, more importantly, it's deeply satisfying. Readers are looking for that kind of fist-pumping moment, whatever the genre or audience.

Determination: How active a character are they?

Some characters let themselves be blown around by the plot. There are instances where this can work, done carefully. But at some point, your protagonist needs to push their own journey forward. Determination can be a powerful factor in wanting to see your character succeed. The odds keep stacking up, but they keep moving forward because they have to, either for their sake or for the world's.

Determination is an important factor for underdog characters or for someone going up against a seemingly invulnerable figure. It's also vital for characters in the same vein as Spider-Man or Captain America--people who keep getting knocked down, but rising up anyway until they can succeed. While they will need some skill sooner or later if they're going to win, that ability to get back up over and over, despite all life has to throw at them, makes audiences want them to succeed.

Another way to put determination: ambition. While greed can be harmful, ambition is not. (And as a Slytherin, this is where I disagree with J.K. Rowling's usual pessimistic portrayal of her most ambitious House.) Is your character ambitious enough to go after what they want, if the antagonist stands in the way? Fighting for what they desire despite the odds can get me cheering for your protagonist.

Determination is an important factor for underdog characters or for someone going up against a seemingly invulnerable figure. It's also vital for characters in the same vein as Spider-Man or Captain America--people who keep getting knocked down, but rising up anyway until they can succeed. While they will need some skill sooner or later if they're going to win, that ability to get back up over and over, despite all life has to throw at them, makes audiences want them to succeed.

Another way to put determination: ambition. While greed can be harmful, ambition is not. (And as a Slytherin, this is where I disagree with J.K. Rowling's usual pessimistic portrayal of her most ambitious House.) Is your character ambitious enough to go after what they want, if the antagonist stands in the way? Fighting for what they desire despite the odds can get me cheering for your protagonist.

You don't need to max out all three traits on each protagonist to have them succeed. Action heroes, for example, probably would make pretty terrible friends in real life. But they're astoundingly competent, most of the time, so we root for them anyway.

Some other examples:

Kvothe from The Name of the Wind is not very likable to me. He's unintentionally unsympathetic in a lot of ways. But he is very competent, which is exciting to watch regardless.

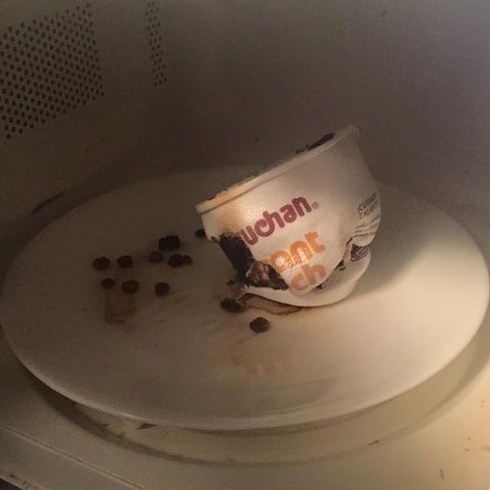

Martin Crieff from the BBC radio drama Cabin Pressure is pretty incompetent (though not as much as Arthur, who can ruin even a simple microwave dinner). As a rule-follower and obsessive control freak--albeit one played by Benedict Cumberbatch--he varies on likability from episode to episode. However, he is bound and determined to be a pilot, and he won't settle for not getting to do what he loves. That determination gets me to root for him, even in a fairly low-stakes sitcom.

Antagonist Traits

Villains share a similar scale. However, the higher they rank on all three, the more terrifying--rather than Sue-ish--they are. Their traits:

- Believability

- Personality

- Competence

Believability: Could this person actually get away with this?

This does not necessarily apply to superpowers or the kinds of weapons they have. It's now they use them, and whether it's believable in-universe.

A villain who is not believable may stretch the suspension of disbelief. A character with no charisma or competence shouldn't be able to boss around generals or an army. If your villain must fill this role, how easy is it for the character to make others do what they want? If they don't start out in this role but grow into it, how do they reach that point so that their actions are believable?

- Remember that, if I may refer to D&D for a moment, charisma also applies to traits like intimidation and physical presence. No one really wants to push back on a villain who has carried out severe punishment for insubordination before.

Personality: What makes them stand out when they walk in a room?

Darth Vader stands out as one of the top film villains because of this. He takes the place of Flash Gordon villains from the 1970s. These were over-the-top, easily-beaten villains, and Star Wars moviegoers might have thought they'd get one of these. Enter an imposing, heavy-breathing figure all in black. He is calm, cold, and unfazed by anything. He even comes close to strangling an admiral just for mouthing off. That's starkly different to what his predecessors were like.

Is your villain lacking in personality? As long as they're believable and competent, and don't take up a lot of page/screen time, they may not need one. In Lord of the Rings (both the books and Peter Jackson's film trilogy), we don't need to see much of Sauron himself or hear him monologuing about his plans to understand that he is a threat. We don't even need much of his backstory at this point. It's enough that he has greedy or fearful allies, a country full of Orcs ready to gut Middle-Earth on command, and the resources to find the One Ring if the Fellowship is not very careful about their journey.

However, if your villain has to confront the hero in person, or if they get to share their POV from time to time, personality becomes a must. A bland, cardboard villain will not be much of a threat to your reader, even if they are incredibly strong.

However, if your villain has to confront the hero in person, or if they get to share their POV from time to time, personality becomes a must. A bland, cardboard villain will not be much of a threat to your reader, even if they are incredibly strong.

Competence: How good a villain are they?

These days, we don't think much of villains who monologue themselves into falling into a vat of acid. They're easily beaten, and therefore not much of a threat. They just aren't entertaining enough, especially against a competent Batman character.

We want villains who pose a real threat to our protagonist and to their world. We want villains who are (seemingly) impossible to outwit or outfight, raising the stakes with every page or episode. If they're too easy to beat, then the audiences may look at the story with a sigh and a "so what?" Worse, if your characters don't have to reach down inside themselves to beat the villain, they probably won't ever grow.

"So what?" indeed.

"So what?" indeed.

Antagonist Analysis

After 22 Marvel films, 13 X-Men films, Christopher Nolan's Dark Knight trilogy, and the beginnings of the DCEU, I am still a fan of superhero films. I am also a big fan of supervillains--the catalysts of the genre. YMMV on the best type of villain across film and book genres, but there is no denying the pull of supervillains and how they often use the best of these elements to go toe-to-toe with the hero.

Wilson Fisk (Netflix's Daredevil)

Fisk doesn't need to command a room from the start as Vader does. He seems unassuming and shy when introduced, and he has a stutter. But he's one of those villains who makes you doubt yourself and the hero, because he believes so forcefully in what he's doing and that he's right. He is also polite and respectful in an almost Hannibal Lecter way. Fisk looks out for those he genuinely cares for, even as he is ruthless in destroying those in his way.

Wilson Fisk throws both his money and his literal weight around to make things happen, turning him both believable and competent in the extreme. It's not hard to think that someone that powerful couldn't make life hard for the little guy to get them vulnerable to his machinations.

Once that mask comes off, Heath Ledger's performance sears the Joker's personality into the audience's minds. He doesn't need to shoot everyone just to get attention; his characterization does that all on its own.

The Joker (The Dark Knight)

The Joker appears with sheer force of personality from the start, although what we see first is his massive competence. He pulls off a heist with barely a word to anyone else, escaping so smoothly that it's easy to believe everything was timed to the last second. Immediately, we can understand what a threat this character is. And within the grimdark Gotham, it seems entirely plausible that he can get away with his actions.Once that mask comes off, Heath Ledger's performance sears the Joker's personality into the audience's minds. He doesn't need to shoot everyone just to get attention; his characterization does that all on its own.

Hela (Thor: Ragnarok)

As soon as Odin drops his last big reveal and--in classic Allfather fashion--nopes out of the story, we get the biggest threat to Asgard in the MCU: Hela.

Hela begins with massive competence by shattering Mjolnir, invading Asgard (RIP Warriors Three), and booting both Thor and Loki out into space. Right away, we know this is a character who will take what she wants--and worse, has both the skill and the right to do so. Thor's triumphal return won't knock her out of power, the way it did with Loki back in the first film. That also adds to her believability: Odin keeps secrets about all his children, so what makes this instance different?

But Hela isn't a cackling madwoman; she's regal, intelligent, and snarky. Among some of the blander villains in the MCU, her personality stands out. It doesn't hurt that she's played by the charismatic Cate Blanchett, either.

Thanos (Avengers: Infinity War)

Spoilers, if you still haven't seen Avengers: Infinity War or the ensuing memes.

This post will NOT contain spoilers for Avengers: Endgame.

Sometimes, villains are competent enough to win. Thanos in Avengers: Infinity War stands as a competent threat to the heroes of the Marvel Cinematic Universe in his goal to wipe out half of all life.

By the end of "Infinity War," they've lost. While they've taken hits, and while some people have died, they have never lost. Thanos is a stark contrast to every other Marvel villain, who've all ended up dead or in prison for their evil machinations.

This post will NOT contain spoilers for Avengers: Endgame.

Sometimes, villains are competent enough to win. Thanos in Avengers: Infinity War stands as a competent threat to the heroes of the Marvel Cinematic Universe in his goal to wipe out half of all life.

By the end of "Infinity War," they've lost. While they've taken hits, and while some people have died, they have never lost. Thanos is a stark contrast to every other Marvel villain, who've all ended up dead or in prison for their evil machinations.